The Zen Art of Sailboat Maintenance

Over the last few years I’ve been trying to get better at sailing. After taking introductory courses and getting out in the local waters for day sails, I started stagnating and decided that in order to gain more experience I needed to crew on bigger boats and call at different ports. As I reflect back on these experiences, I realize that after the vastly different boats, captains, and crew-mates; there is a surprising amount of similarities between boat life and startup/corporate life.

I want to share some of these parallels through the tale of two of the boats (both wooden schooners). At the surface, they couldn’t be more different, but they both taught me helpful lessons about leadership, teams, and mission. Aboard them I also understood the “Zen Art of Sailboat Maintenance” and how to be content with my career.

The Protagonists

Galaxy is a 40-ton 60-foot Turkish Gulet (ketch) owned by Arnaud, a middle-aged swiss banker whose rapidly deteriorating eyesight motivated him to go see the world. He traded his fiduciary obligations to learn about ‘supra-light’ communication and ‘energy healing’. Galaxy’s master is charismatic and athletic. He has single handedly sailed through pirate infested waters of Somalia, and is legally blind after sunset. He makes friends wherever he goes, and occasionally takes on people to help him with night sailing and fending off boredom.

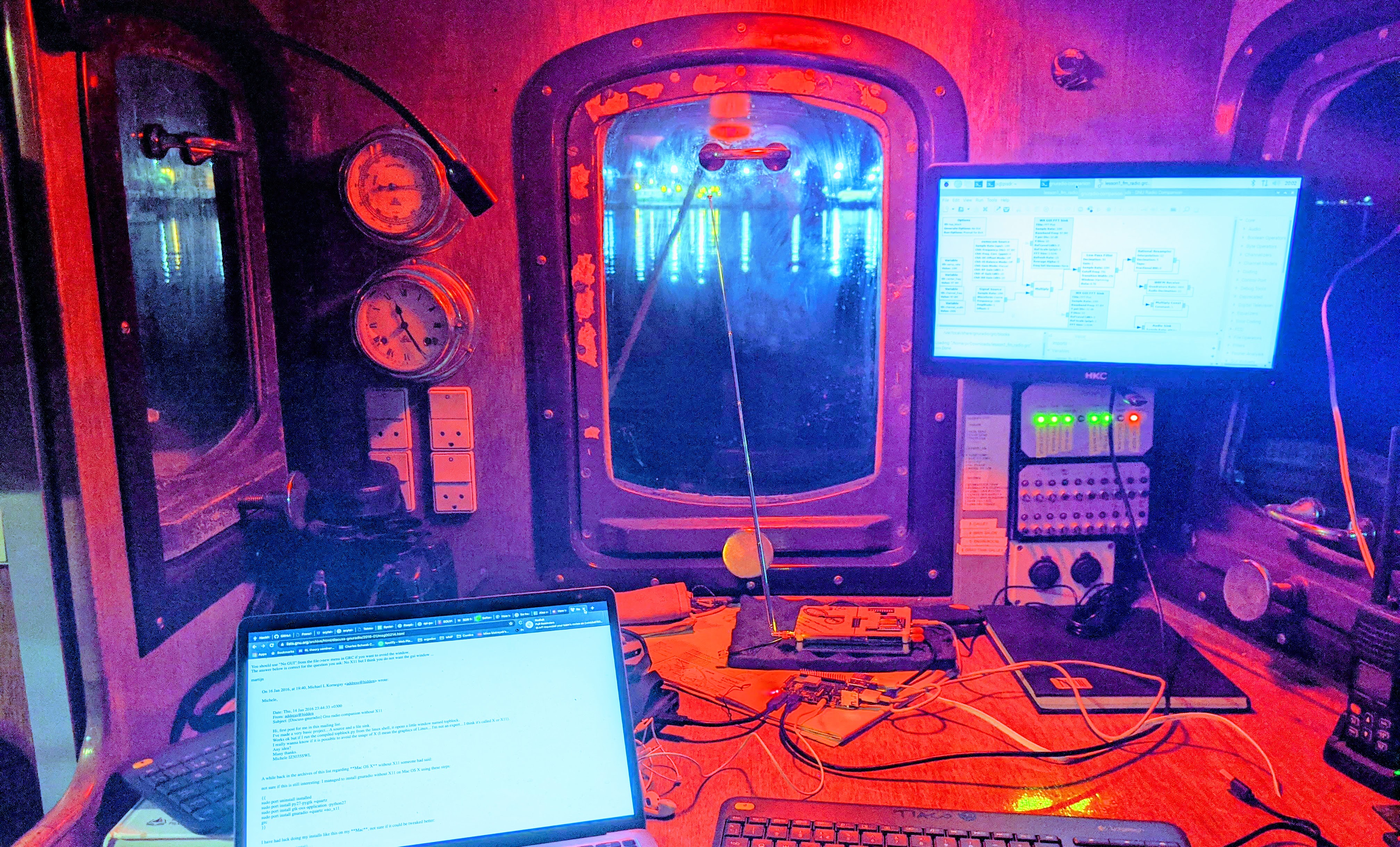

Labora is a 60-ton 70-foot Danish fishing boat that was rebuilt in the 80s as a gaff-rigged ketch and mostly kept at dock for entertaining guests. It was recently purchased by Doug, an old Alaskan adventurer who never owned a bank account. Doug has made his living from working on fishing boats, making documentaries in Borneo and the Brazilian Amazon in the 70s, trapping, and “farming”. He is hard of hearing, can’t afford to repair his ear-piece, and in the two years he has owned Labora, he has hosted over 200 people as crew.

Galaxy could be sailed single handedly, while Labora required a minimum of five crew just to raise the main sail. Galaxy was water tight and had two beautiful purring V8 engines. Labora’s bilge pumps were frequently burning out as they battled the leaking rudder post and greasy gray box, and its Caterpillar engine had trouble starting due to its leaking fuel filters.

One captain had an aversion to modern medicine and swore by pumpkin seed oil, the other constantly took pain killers to dull his hip pain and perused far right conspiracy websites. One was an adventurous eater and great cook, the other couldn’t handle spices and never did the dishes. You could have open and honest conversations with one, while the other was passive aggressive. One is happy to follow the winds and enjoy the journey, the other is on a mission to get back to Brazil at any cost.

I like to think of Galaxy as one of those startups backed by tech billionaires: well-funded, headed by a charismatic serial entrepreneur, not worried about when it needs to reach its destination as it has the luxury to wait for the right hire, the right conditions, and take its time to find product market fit. Labora is instead the pretty-on-the-outside-toxic-in-the-inside corporate division which keeps losing its employees. It’s held together by the sheer will of its director, who continuously manages to convince a new wave of employees and upper-management that if only they all make sacrifices, they’ll reach the promised land. Never mind the duct-taped demo (cracking mast) or the constant cost overruns (debt to previous crew).

But I digress… I want to focus on what it was like to live with and “work” for these different personalities. Both were self-proclaimed teachers, with a healthy amount of narcissism. So it’s no surprise that they taught me a lot about rigging, engines, fixing pumps, tying knots, dealing with conflict, and living with uncertainty.

Conflict Resolution

With Arnaud, I quickly realized that our appetites for risk were different. As soon as we boarded in Zanzibar, he told us about his plan to sail up to the Kenyan border with Somalia to meet a half-dozen boats for a new-moon party. Soon followed an intense but open conversation about our goals and desires from the trip, which set the stage for the weeks to follow.

Indeed, during my time there we’d often disagree about the what, how, and when of everything. But we would discuss the options and Arnaud would retreat to his quarters to ‘wait for the answer’ to come to him. It was frustrating at first to not be able to convince him on the spot of my point of view despite my ‘rational’ arguments; but in retrospect, by taking these moments to think, it created space and time for his decisions to feel less arbitrary, and to give them a sense of commitment.

Arnaud constantly reminded me that on a boat, just like in life, not all problems require ‘optimal’ solutions and not all decisions can be data-driven. I also had to remember the old adage of ‘disagree but commit’: the alternative on a boat is mutiny and potentially the plank!

Suffice to say, there were tons of opportunities to practice conflict resolution, negotiation, and open communication. In the end, we managed to have plenty of adventure and excitment for all of us while successfully avoiding the ship getting boarded by pirates (although we’d eventually get boarded by Tanzanian immigration officials, which Arnaud argued was far worse!)

Arnaud and I thought very differently about the world and had opposite approaches when it came to making decisions. We nonetheless got along because we communicated and respected each other, understanding what each wanted out of the adventure. Even though we never had a clear long-term destination (mostly exploring mangroves, chatting up locals, and sometimes anchored days at a time waiting for spring tides to go through shallow channels), it was one of my most memorable adventures.

Team and Mission

In contrast to Arnaud who is “circumnavigating” without a clear destination (two years later Galaxy is still cruising in the Indian Ocean), Doug was on a clear mission: recreate his younger self’s adventure by mounting an expedition up the Amazon in Brazil. And unlike Galaxy where the only other crew was my wife Olivia, on Labora we were a half-dozen poor lost souls on board.

I decided to join Labora with the aim to get some offshore experience crossing from Spain to the Canary Islands. Shortly after I came aboard, I heard of the stories of others who before me, hmm, jumped ship. Most revolved around how the captain was dishonest and toxic. As a new comer, I decided to give him the benefit of the doubt, but sure enough, two days later and I was thinking about packing my gear.

Coincidentally, the day before I arrived, another crew joined: Jonas, a German ‘traveling teacher’ with long hair hitchhiking across Europe. Jonas had experience living in communal groups, and although he was taking more abuse from the captain because he was a novice sailor, his willingness to name and challenge the problem led to the crew bonding together. It was to be a rare moment in Labora’s long history of rotating deck hands where six of us were motivated to push against the adversity to prepare the boat for a crossing.

We had a mission to rally around, and we self-organized into sub-teams, set OKRs (fine we didn’t call them that), had brainstorming sessions to solve problems, and even did performance check-ins. We bought EPIRBs and fire extinguishers, plugged leaks, rigged square sails, practiced reefing the main and mizzen, updated the med-kit, replaced and rewired the bilge pumps, and started provisioning for the Canaries.

Unfortunately, this would only last two weeks during which the captain, perceiving our bonding and self-organizing as a challenge to his authority and divide-and-conquer leadership style, progressively drove a wedge and sowed conflict. Between his continuing dishonesty, verbal abuse to some, passive aggressiveness to others, and gear that was supposedly ordered but never arrived; the thru-hulls started to leak: we weren’t going to meet the ship doctor’s deadline, I was close to overstaying my Schengen visa, a young apprentice was fed up with the abuse, a new crew with a different attitude joined, we didn’t have money for fuel yet the captain insisted on buying fishing gear,and despite his daily introspections and meditations Jonas cracked sending morale down.

Four of us ended up leaving within a week of each other, leaving the boat shorthanded. But shortly thereafter another round of crew joined, lured by the dream of an Atlantic crossing (Almost a year later, Labora still hasn’t crossed: it made it to the Canaries four weeks after I left and is now stuck in Cape Verde) Doug would come to see this as a validation of his leadership style: drive people hard and don’t worry about them burning out, everyone eventually leaves but that’s ok as there will always be others who will join.

I almost left Labora after two days of arriving due to the captain’s attitude, and I’m not sure I would have made the crossing as I didn’t trust his judgment. But despite that I stayed for a month because I found a tribe and a purpose.

The Art of Zen

There is a special Zen in waking up to a deck bell, working hard with excited teammates, chowing down brunch (which you don’t get to pick from a menu), fixing whatever is on the ‘get-to-the-canaries’ list, rinsing the sweat, and finishing the day singing sea shanties around a hot meal.

The Zen is a moment where the concerns of career advancement, worries of whether salary/benefits are fair, or success relative to peers are not top of mind. Instead, there is joy and pride in the hard work (whether it is coding optimization algorithms or scraping barnacles off the hull) alongside a group of people you share a special bond with, towards an exciting missions, and with a captain that you trust.

The Zen is hard to come by: vetting the ‘culture’ of a boat from calls with the captain and sailing forums is as hard as doing so for a company through interviews and glassdoor reviews. It is equally hard to maintain as teams grow, missions change, and leaders come an go.

Finally, the Zen by itself is not enough. I found it shoveling horse manure in stables in Portugal, and doing scientific diving in Mozambique, but there I had neither team nor exciting challenges and quickly lost interest. Likewise, I found the Zen in my freelancing days working on challenging technical problems with various fun teams, but found myself itching for a sense of mission.

Today, as I embark on a new adventure at a company that had ‘Zen’ at the core of its culture in its early days, I am encouraged by how they have preserved some aspects of it as they continued to grow, and hopeful that here too I will find a tribe and purpose as we brave the choppy waters ahead.